Cassandra’s Data Model#

Jeff Carpenter, Eben Hewitt - Cassandra The Definitive Guide, Third Edition Distributed Data at Web Scale - O’Reilly Media (2022)

But the structure you’ve built so far works only if you have one instance of a given entity, such as a single person, user, hotel, or tweet. It doesn’t give you much if you want to store multiple entities with the same structure, which is certainly what you want to do. There’s nothing to unify some collection of name/value pairs, and no way to repeat the same column names. So you need something that will group some of the column values together in a distinctly addressable group. You need a key to reference a group of columns that should be treated together as a set. You need rows. Then,

if you get a single row,

you can get all of the name/value pairs for a single entity at once,

or just get the values for the names you’re interested in.

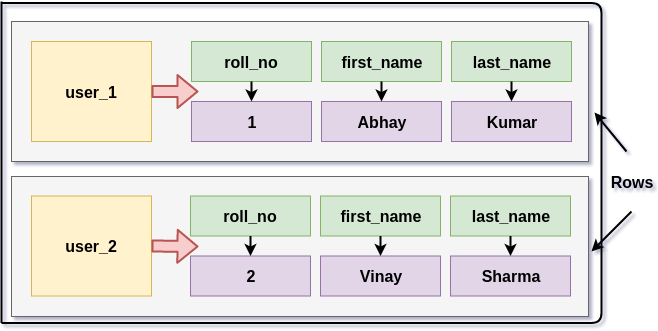

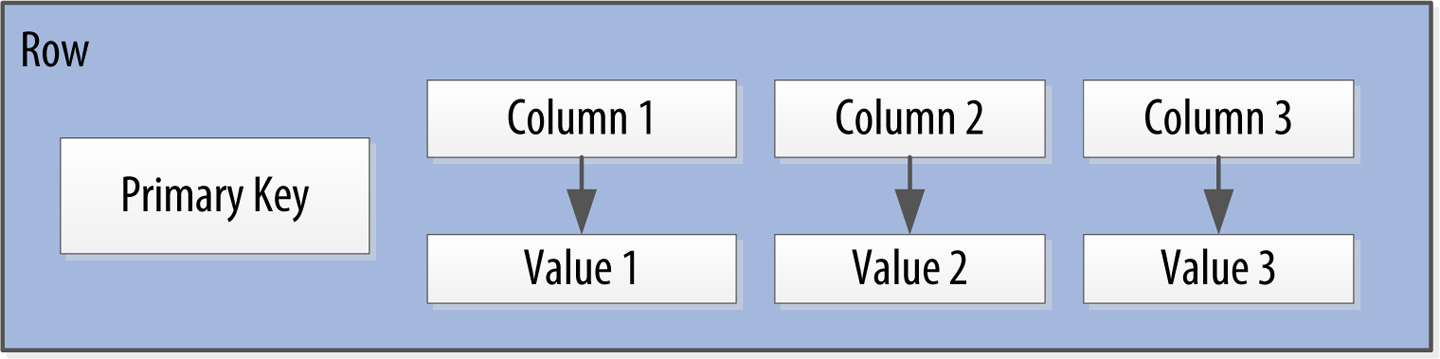

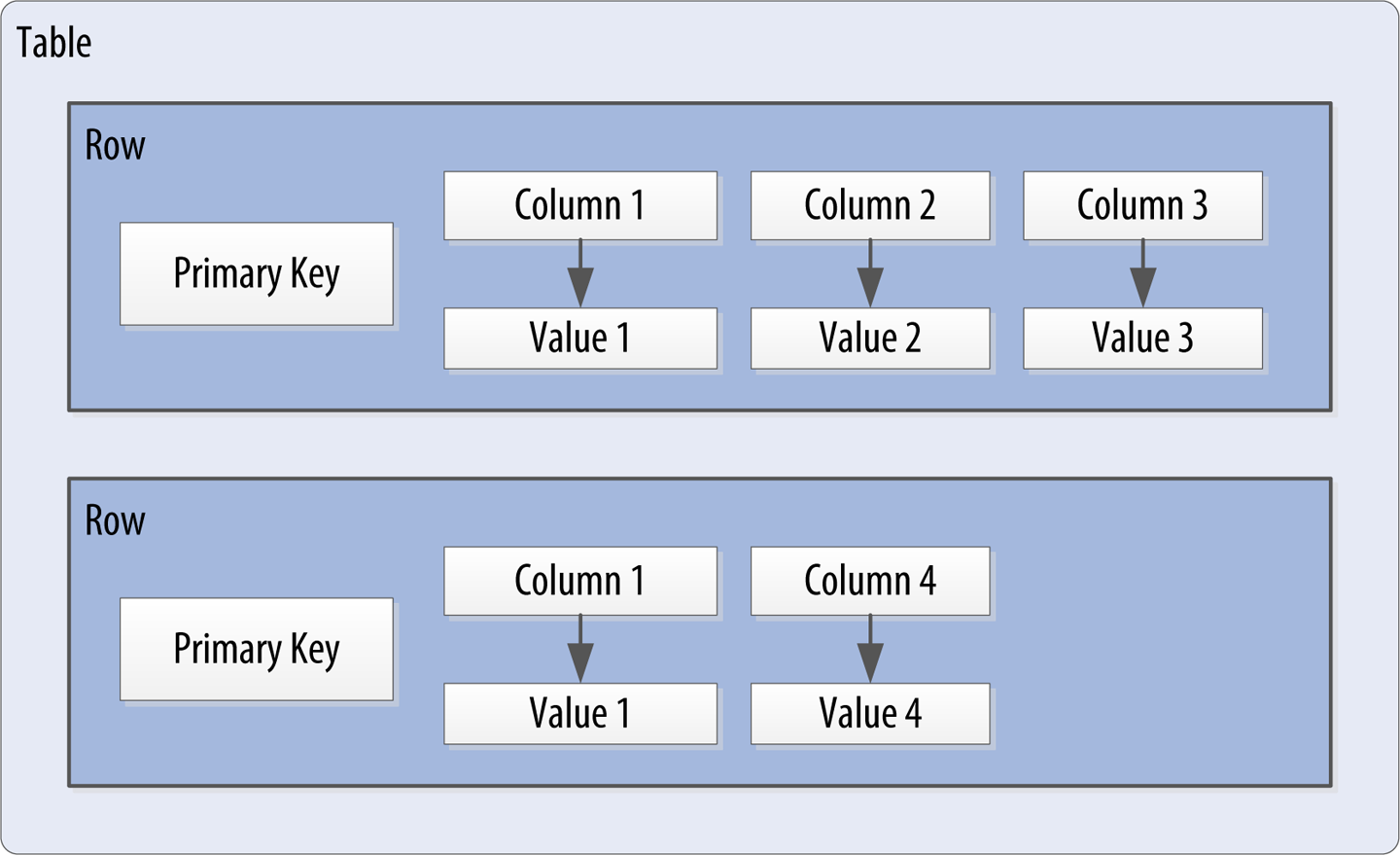

You could call these name/value pairs columns. You could call each separate entity that holds some set of columns rows. And the unique identifier for each row could be called a row key or primary key. Figure 4-3 shows the contents of a simple row: a primary key, which is itself one or more columns, and additional columns. Let’s come back to the primary key shortly.

Figure 4-3. A Cassandra row

Cassandra defines a table to be a logical division that associates similar data. For example, you might have a user table, a hotel table, an address book table, and so on. In this way, a Cassandra table is analogous to a table in the relational world.

You don’t need to store a value for every column every time you store a new entity. Maybe you don’t know the values for every column for a given entity. For example, some people have a second phone number and some don’t, and in an online form backed by Cassandra, there may be some fields that are optional and some that are required. That’s OK. Instead of storing null for those values you don’t know, which would waste space, you just don’t store that column at all for that row. So now you have a sparse(疏), multidimensional array structure that looks like Figure 4-4. This flexible data structure is characteristic of Cassandra and other databases classified as wide column stores.

Now let’s return to the discussion of primary keys in Cassandra, as this is a fundamental topic that will affect your understanding of Cassandra’s architecture and data model, how Cassandra reads and writes data, and how it is able to scale.

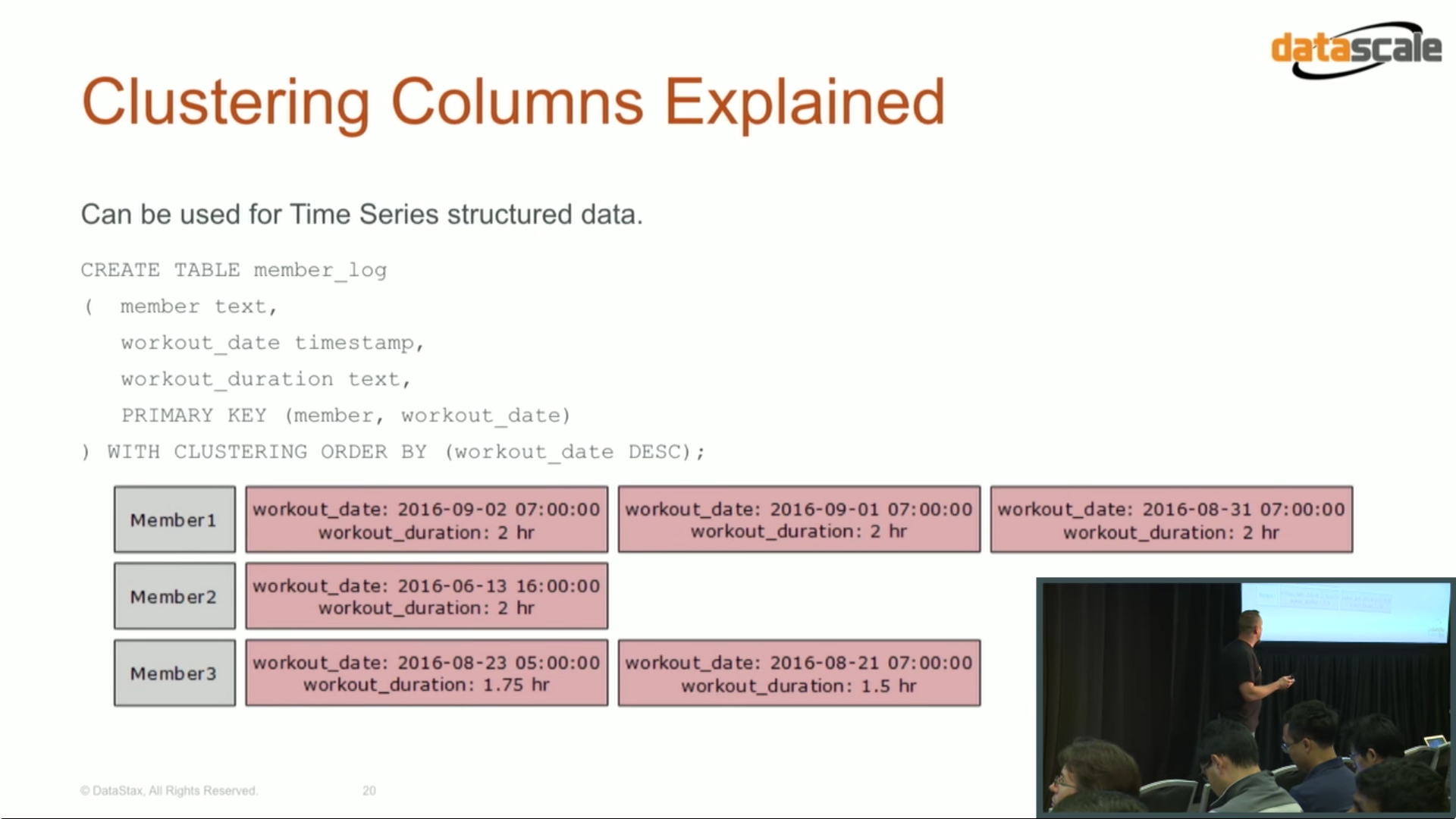

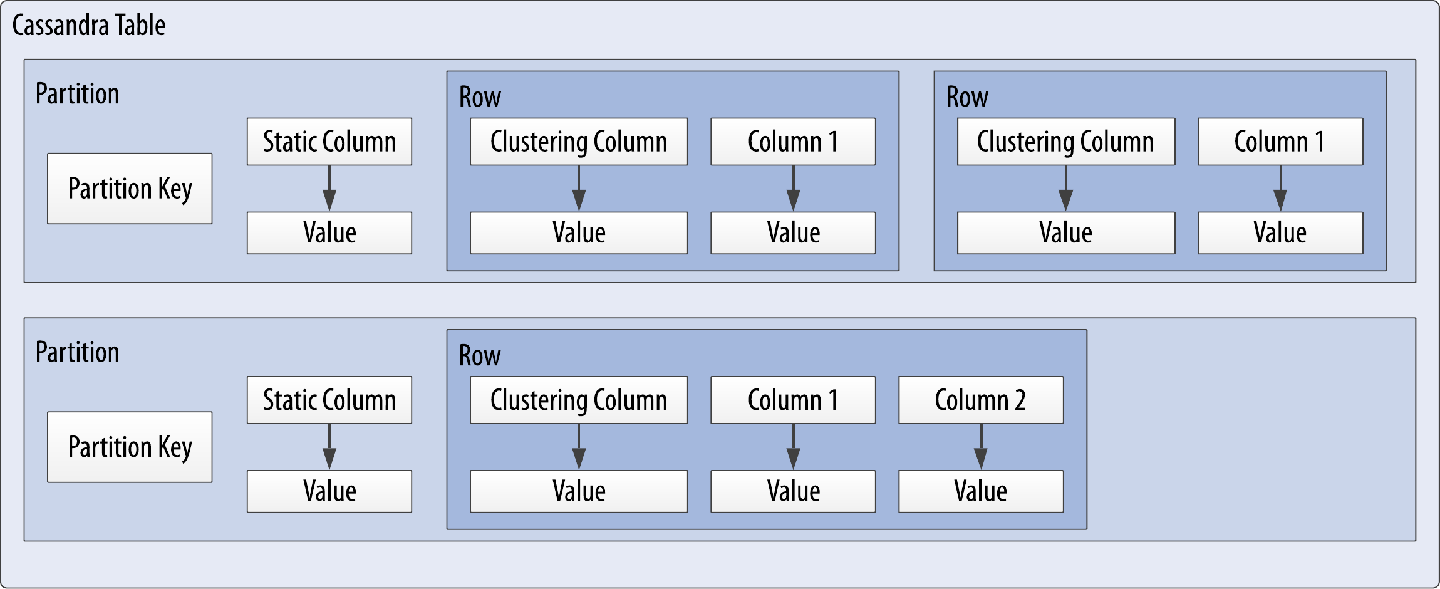

Cassandra uses a special type of primary key called a composite key (or compound key) to represent groups of related rows, also called partitions. The composite key consists of a partition key, plus an optional set of clustering columns. The partition key is used to determine the nodes on which rows are stored and can itself consist of multiple columns. The clustering columns are used to control how data is sorted for storage within a partition. Cassandra also supports an additional construct called a static column, which is for storing data that is not part of the primary key but is shared by every row in a partition.

Figure 4-4. A Cassandra table

Figure 4-5 shows how each partition is uniquely identified by a partition key, and how the clustering keys are used to uniquely identify the rows within a partition. Note that in the case where no clustering columns are provided, each partition consists of a single row.

Figure 4-5. A Cassandra table with partitions

http://sudotutorials.com/tutorials/cassandra/cassandra-primary-key-cluster-key-partition-key.html

CREATE TABLE users (`` ``userid text PRIMARY KEY,`` ``roll_no ``int``,`` ``first_name text,`` ``last_name text``);When a table has single primary key, Cassandra uses one column name as the partition key.

Putting these concepts all together, we have the basic Cassandra data structures:

The column, which is a name/value pair

The row, which is a container for columns referenced by a primary key

The partition, which is a group of related rows that are stored together on the same nodes

The table, which is a container for rows organized by partitions

The keyspace, which is a container for tables

The cluster, which is a container for keyspaces that spans one or more nodes

So that’s the bottom-up approach to looking at Cassandra’s data model. Now that you know the basic terminology, let’s examine each structure in more detail.

A wide row means a row that has lots and lots (perhaps tens of thousands or even

millions) of columns

composite key (or compound key) : Cassandra uses a special primary key called a composite key (or compound key)

The composite key consists of a partition key, plus an optional set of clustering columns

The partition key is used to determine the nodes on which rows are stored and can itself consist of multiple columns.

The clustering columns are used to control how data is sorted for storage within a parti‐tion

Columns#

A column is the most basic unit of data structure in the Cassandra data model. So far you’ve seen that a column contains a name and a value. You constrain each of the values to be of a particular type when you define the column. You’ll want to dig into the various types that are available for each column, but first let’s take a look into some other attributes of a column that we haven’t discussed yet: timestamps and time to live. These attributes are key to understanding how Cassandra uses time to keep data current.

Timestamps#

Each time you write data into Cassandra, a timestamp, in microseconds, is generated for each column value that is inserted or updated. Internally, Cassandra uses these timestamps for resolving any conflicting changes that are made to the same value, in what is frequently referred to as a last write wins approach.

Let’s view the timestamps that were generated for previous writes by adding the writetime() function to the SELECT command for the title column, plus a couple of other values for context:

cqlsh:my_keyspace> SELECT first_name, last_name, title, writetime(title)

FROM user;

first_name | last_name | title | writetime(title)

------------+-----------+-------+------------------

Mary | Rodriguez | null | null

Bill | Nguyen | Mr. | 1567876680189474

Wanda | Nguyen | Mrs. | 1567874109804754

(3 rows)

Time to live (TTL)#

One very powerful feature that Cassandra provides is the ability to expire data that is no longer needed. This expiration is very flexible and works at the level of individual column values. The time to live (or TTL) is a value that Cassandra stores for each column value to indicate how long to keep the value.

The TTL value defaults to null, meaning that data that is written will not expire. Let’s show this by adding the TTL() function to a SELECT command in cqlsh to see the TTL value for Mary’s title:

cqlsh:my_keyspace> SELECT first_name, last_name, TTL(title)

FROM user WHERE first_name = 'Mary' AND last_name = 'Rodriguez';

first_name | last_name | ttl(title)

------------+-----------+------------

Mary | Rodriguez | null

(1 rows)

Using TTL#

Remember that TTL is stored on a per-column level for nonprimary key columns. There is currently no mechanism for setting TTL at a row level directly after the initial insert; you would instead need to reinsert the row, taking advantage of Cassandra’s upsert behavior. As with the timestamp, there is no way to obtain or set the TTL value of a primary key column, and the TTL can only be set for a column when you provide a value for the column.

The behavior of Cassandra’s TTL feature can be somewhat nonintuitive, especially in cases where you are updating an existing row. Rahul Kumar’s blog “Cassandra TTL intricacies and usage by examples” does a great job of summarizing the effects of TTL in a number of different cases.